Artistic Inspiration Beyond the Visible: PSI in Art

There exist diverse connections between art and PSI. The creative force allows access to a realm hidden from our primary conscious, active senses. Art provides the opportunity to establish a simple and natural communication pathway between the subconscious and consciousness. Moreover, it allows for coupling with the matrix to express impressions of distant places or personalities. Altered states or consciously induced manipulations of consciousness to evoke PSI abilities are particularly natural and integral components of the scientifically protocol-based method, especially in remote viewing. Upon closer examination, a strong connection between art, artists, and PSI phenomena becomes evident. Many PSI-gifted individuals and Remote Viewers are also active in creative, artistic fields. We will delve into why this is the case and explore the historical figures who played a significant role.

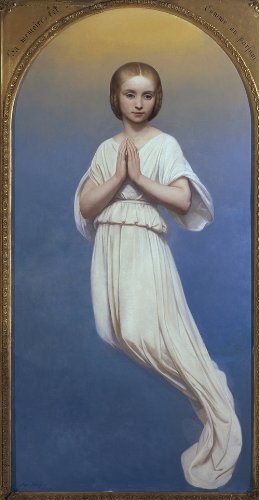

L’Europe des Esprits ou la fascination de l’occulte

Ary Scheffer: “Angel figure representing Mademoiselle de Montblanc after her death

Let’s start with a result of collaboration among dozens of museums and galleries from 13 different countries. The catalog „L’Europe des Esprits ou la fascination de l’occulte. 1750-1950“ is a multidisciplinary exhibition that investigates the influence of the occult on artists, thinkers, and scientists throughout Europe during the crucial epochs of modern history.

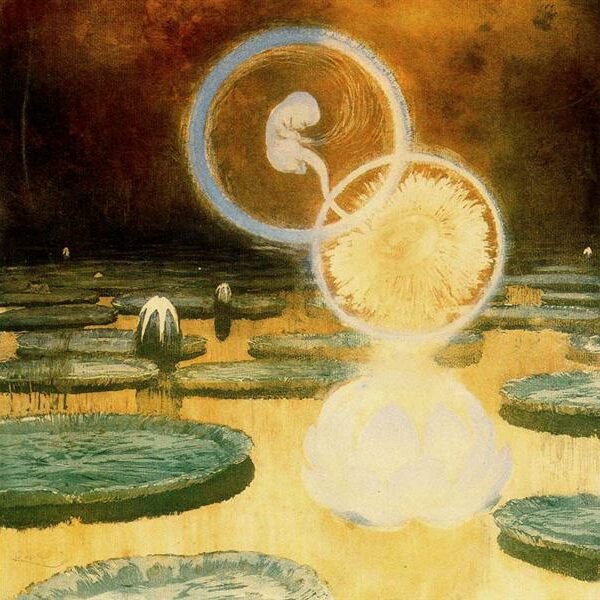

„There is something that comes from so much further than humans and also goes so much further,“ wrote André Breton. The fascination with the unreal and dark, seemingly as old as humanity itself, has been particularly expressed in art. However, this occurred at a time when Enlightenment sciences claimed to illuminate the world in a rational manner, leading to reactions of spiritualism with the early Romantics. The curious often confuse what they do not understand with what they want to believe in spirits, fairies, or demons. William Blake was visited by spirits, and Goethe attempted to fathom the secrets of living materials and colors. With Novalis, who speaks of magical art, the artist sees themselves as a seer or medium. In the 19th century, the phenomenon of Spiritualism emerged, and Victor Hugo was one of the first to engage with spirits through the medium of turning tables. Spiritualism rapidly gained popularity and found a leading theorist in Allan Kardec and his book „The Spirits‘ Book“ (1857).

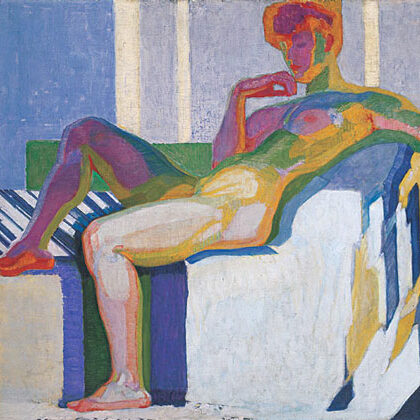

This era was rich in themes such as fairies, demons, vampires, spirits, possessions, and communication with the dead, providing an endless source for artistic representations. Artistic movements like the Symbolists and Nabis, led by the mystical writer Édouard Schuré from Strasbourg, as well as various creative fields such as literature, architecture, dance, music from Mozart to Wagner, Satie to Varèse, photography, and the emerging cinema from Méliès to Fritz Lang were influenced by these same forces. The turn of the century was marked by intense discussions on mediumship and parapsychological phenomena. Some artists, including committed Spiritualists like Conan Doyle or Hilma af Klint, actively engaged with these ideas. Theosophy influenced artists like the Czech painter Frantisek Kupka temporarily and had a lasting impact on painters like Piet Mondrian or Theo van Doesburg. In Germany, modern artist groups like the Blue Rider also appealed to Theosophy, including artists like Kandinsky or Arp.

Artists as Mediums in "Psychic" Arts

Susan Hiller “Dream Machine”

A contemporary artist, Susan Hiller (March 7, 1940 – January 28, 2019), deserves special mention. She combined a critical and skeptical mind with an interest in overlooked, marginal, and irrational aspects of culture. An example of her work is the curation of the exhibition „Dream Machines“ (Hiller & Fischer, 2000), which delved into the transformative power of art, altering the viewers‘ consciousness and inducing different states of awareness.

„I am committed to working with spirits, meaning cultural cast-offs, fragments, and things that are invisible to most people but intensely significant to some. Situations, ideas, and experiences that collectively haunt us“ (Hiller, 2011).

Many artists from the past to the present have dedicated themselves intensely to meditation and shamanic practices to draw inspiration.

“The artist could then make the viewer see the film of his rich, subjective inner world and render the current process of creating a painting or sculpture unnecessary” …

… (according to Daniels, 2002), noted the Czech artist Frantisek Kupka (1871 – 1957), one of the pioneers of abstract painting. He worked as a professional medium from a young age and devoted his entire life to spiritualism. In this way, he opened up a potential perspective to realize art through telepathy, through direct transmission from person to person, without the need for an external object.

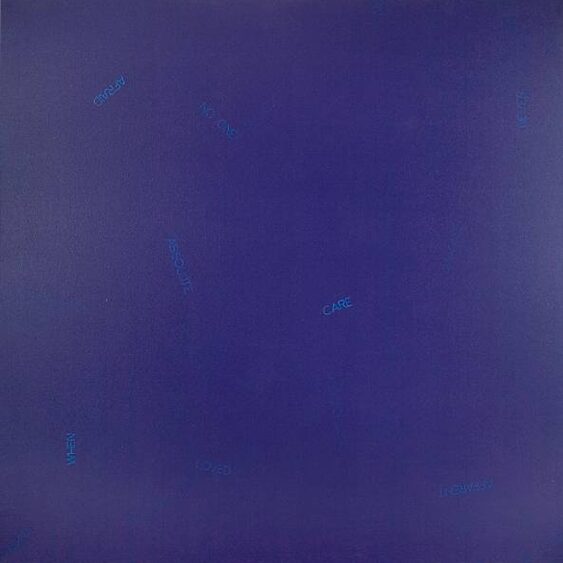

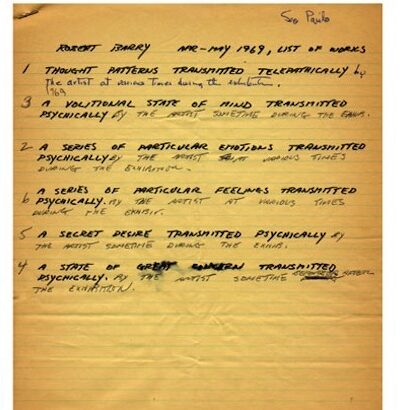

Conceptual artist Robert Barry attempted something similar in his Telepathic Piece of 1969. He reported that during the exhibition, he tried to “telepathically communicate a work of art whose nature is a series of thoughts not applicable to language or image.” At the end of the exhibition, information about the artwork was published in the catalog (Lippard, 1973, p. 98). Image optional.

Performer Marina Abramović commented, “I had the idea of how art could exist in the future. You could tune your body so precisely and use your inner forces to transmit your image, your mental concept, to the viewer or the person you want to convey the message to” (in Phipps, 1981).

Visual artist, critic, and curator Andrej Tisma stated (1992): “Through mental resonance, the artist puts the viewer into a state of fascination, just like the artist himself […] Such experiences, where the artist directly transmits their inspiration, can rightfully be called spiritual art.”

PSI Phenomena in the Lives and Works of Artists

To explore or comprehend a connected, timeless, and spaceless realm (or the “hidden order,” borrowing the term from physicist David Bohm), writers, artists, and musicians have employed various strategies to alter their ordinary state of consciousness (Cardeña & Winkelman, 2011; Iribas, 2000; Iribas-Rudín, 2008). These strategies include experiments with table-tapping and various automatisms, although artists have also spontaneously experienced apparent PSI phenomena.

It appears that artists are overrepresented among individuals who have presented evidence for PSI phenomena in the context of controlled research. Mrs. Leonard, one of the most extensively studied mediums who provided evident material during the early part of the 20th century, attempted to be a professional singer but had to shift to acting after encountering vocal problems (Leonard, 1931/1989). One of the pioneers of psychic research in France was the sculptor and attaché at the Russian Embassy, Serge Youriévitch. Pascal Forthuny, the pseudonym of Georges Cochet, was a writer, painter, and musician who piqued Breton’s interest in PSI. He was tested at both the Institut Métapsychique and the Society for Psychical Research, achieving exceptional performances in clairvoyance and psychometry in both (Méheust, 1999).

Two individuals associated with the Remote Viewing program at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) were artists: Hella Hammid, a photographer, and Ingo Swann, a painter who developed the Remote Viewing method with Russell Targ and Harold Puthoff.

Professional artists or those sincerely interested in art have also contributed as researchers, including some of the most significant figures in the history of parapsychology: William James, who worked as a painter for over a year, and whose prose would make most writers turn green with envy; F. W. H. Myers, an award-winning poet; Edmund Gurney, a music theorist; and Lady Una Troubridge, a sculptor and translator who penned one of the most fascinating analyses of consciousness changes in trance mediums (1922).

Controlled PSI research supports the conclusion that the apparent overrepresentation of artists among individuals gifted with psi is not a coincidence. Regarding subjective paranormal experiences (experiences of alleged psi that were not formally tested), Holt, Delanoy, and Roe (2004) administered questionnaires on creativity and other variables to 211 participants, including professional artists. A factor analysis revealed that potential parapsychological experiences loaded on a factor of “intrapersonal awareness,” which also included several other anomalous experiences such as mystical encounters and dissociation. This factor significantly correlated with emotional creativity, heightened inner awareness, and nonlinear cognition, showing a significant association with literary and visual arts, while the correlation with performing arts was not significant.

In the second half of the 19th century, the modern spiritualist movement spread in Europe, partly due to the involvement of several renowned writers. Several significant British writers were members of the Ghost Club, founded in 1862 and still active, including the poet Siegfried Sassoon, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and the author Charles Dickens. The latter famously wrote many ghost stories, such as “A Christmas Carol” and “The Signal-Man.”

Maurice Maeterlinck from Belgium, who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911, was convinced of the validity of PSI phenomena. Similarly, the French philosopher Henri Bergson, awarded in 1927 and concurrently the President of the Society for Psychical Research, shared similar beliefs. Another significant Nobel laureate (1923) who supported the reality of psychic phenomena was the Irishman William Butler Yeats. Between 1887 and 1905, he played a significant role in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and authored rituals of magical practices for the Order, influenced by the works of William Blake, which he published during that time (Werblowsky, 1970). Another example is the renowned American author Upton Sinclair (1930–2001), who wrote the book “Mental Radio” about telepathy experiments with his wife, with an introduction by Albert Einstein.

Significant artists have shown interest in PSI phenomena, incorporating them into their work and providing indications of Psi in their lives through controlled research.

In summary

Research has suggested that artists tend to be more emotional, sensitive, independent, impulsive, unconventional, and introverted compared to other professions (Abuhamdeh & Csikszentmihalyi, 2004). These characteristics increase the likelihood that artists can perceive subtle PSI information and are less inclined to ignore it to conform to skeptical positions. By definition, artists might also be more prone to discovering or creating patterns more easily than others, akin to what shamans seem to do (Shweder, 1972), and therefore, interpret some coincidences as meaningful rather than random events, regardless of the actual ontology of these events.

Another aspect that could explain why artists often report Psi phenomena is their tendency to experience alterations in consciousness. For example, compared to other professional groups such as engineers, artists have thinner mental boundaries. This means they do not experience rigid boundaries between psychological processes like states of consciousness (awake and asleep) or a sense of self and others (Hartmann, 1991). Studies have found a connection between thin mental boundaries (more “Thin Subjective Experience” than “Attitudinal Thinness,” see Cardeña & Terhune, 2008) and reporting paranormal experiences (Houran, Thalbourne & Hartmann, 2003).

References and Further Reading